Pipits have been on the move in recent weeks. Of the four pipits that regularly occur in Poole Harbour, two are resident, one is a summer visitor and the other is a scarce winter visitor. Meadow Pipits, often referred to as Mipit by birders, can be seen all year around. During the summer months, Meadow Pipits breed across our local heathlands, with strong populations at Arne, Studland and Godlingston. Numbers fluctuate in autumn and winter, especially out on open heathland where numerous feeding flocks of 50+ individuals assemble during the winter. Autumn passage can be an impressive spectacle, with counts of 500+ over the harbour during favourable vis-mig conditions. Much like with the finches we discussed several weeks ago, early morning visits to North Haven, South Haven and Ballard Down during September and October are best when looking to connect with large numbers of passage birds.

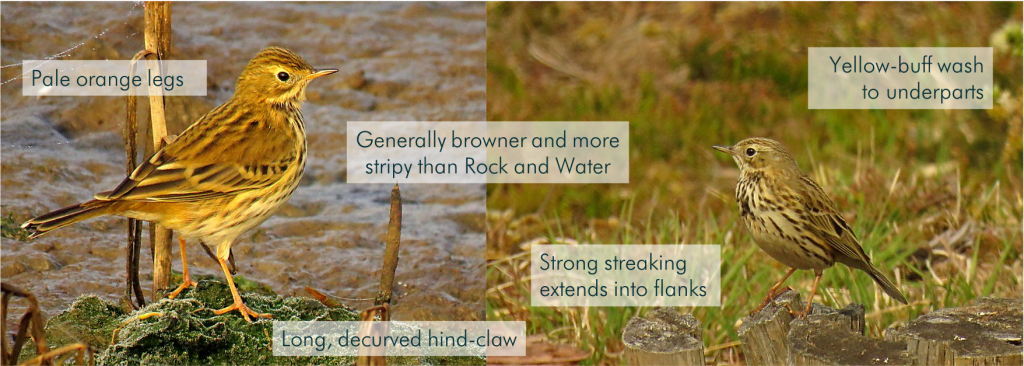

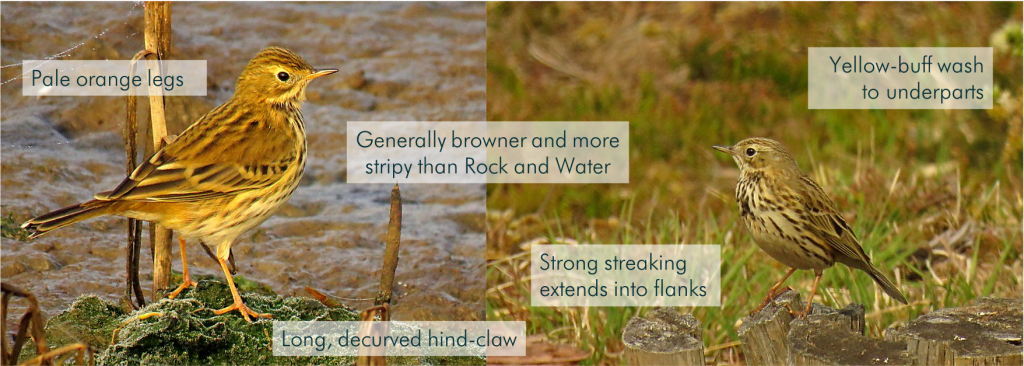

Despite being widely under-appreciated, disregarded as small, brown and squeaky, Meadow Pipit plumage is in fact an immaculate rich olive-brown, complimented by a yellow-based bill and pale pinkish legs. Their resident status unfortunately shrouds the considerable movements these attractive pipits undertake at this time of year. Estimates put the breeding population in Britain and Ireland at approximately 2.5 million pairs, and the wintering population at more than half this. Sizeable numbers (over 450,000) have been ringed in Britain and Ireland, but only a fraction are recovered. This is considered to be due to their excellent camouflage plumage and the remote areas Meadow Pipits frequent. On the plus side, Meadow Pipits are amongst the most conspicuous daytime migrants, not least because of there piercing seet flight calls, and this assists in plotting there migratory flyways.

Ring-recoveries and observations reveal a steady southward movement spanning July to October and November. Some of the British breeding population do not leave our shores for the winter, and simply leave the inhospitable uplands in search of milder lowland areas, such as Poole Harbour. Those that leave Britain head typically move south into France and then southwest into the Iberian Peninsula, some even crossing over into North Africa! Movements of British birds are augmented in spring and autumn by birds en route to and from Scandinavia and Iceland.

Meadow Pipit. Photo © Ian Ballam

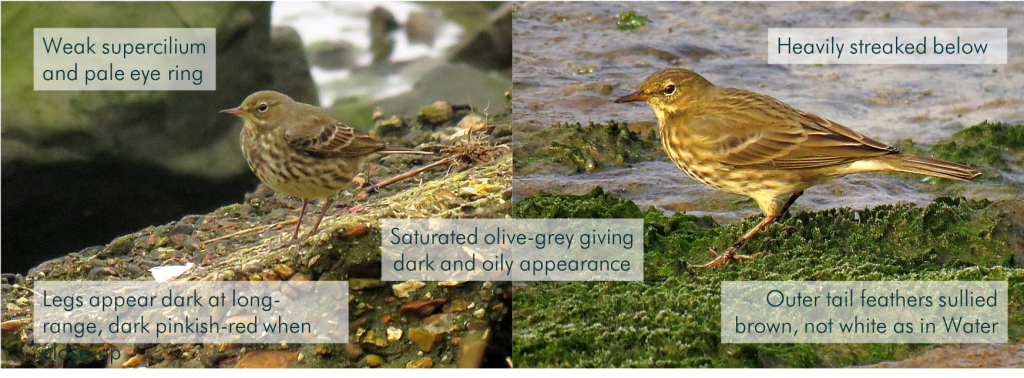

Rock and Water Pipits are visually and audibly very similar, both are more easily separated from the commoner Meadow Pipit in being bulkier, more upright birds with longer legs and a noticeably longer, more dagger-like bills. In flight, Meadow Pipit are shorter-winged and shorter-tailed, with a more hesitant flight. Flight calls are helpful when separating Meadow Pipit. Both Rock and Water Pipit give a strident single pseep, whilst the thinner Meadow Pipit call is a string of more feeble seep notes, generally delivered in pairs or triplets.

Meadow Pipit flight call

From Catching the Bug web-book © The Sound Approach

Rock Pipit flight call

From Catching the Bug web-book © The Sound Approach

Water Pipit flight call

From Catching the Bug web-book © The Sound Approach

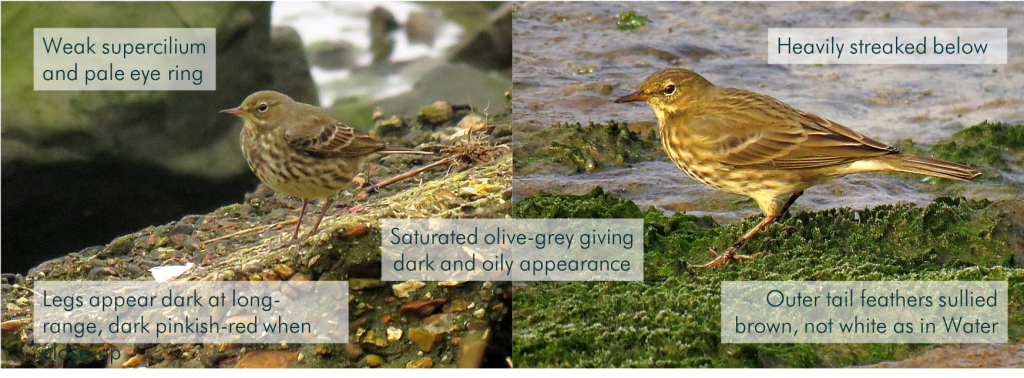

Locally, Rock Pipits breed on cliffs around Ballard Down where they can be encountered throughout the year in small numbers. Rock Pipits are widely recorded during winter on the saltings across the harbour, sometimes in large numbers, with 60 recorded at Swineham on November 26, 1989 and 50 at Lytchett Bay on December 18, 2005. In spring, when these birds begin to acquire their summer plumage, it is apparent that many, if not all, are in fact Scandinavian Rock Pipits (race littoralis). Unlike our British birds, which are highly sedentary, Scandinavian littoralis are a separate subspecies that breed in – you guessed it – Scandinavia. February 22, 2016 saw eight spring plumage (presumed) littoralis Rock Pipits at Lytchett Bay. Ringing data from the Bay also supports these observations with two birds recovered with foreign jewellery, one with a Norwegian ring and the other with a Belgian ring (captured and ringed on migration from Scandinavia en route to its British winter grounds).

Rock Pipit. Photo © Ian Ballam

Previously considered a subspecies of Rock Pipit, Water Pipit was granted full species status in 1986. Water Pipits are scarce seasonal visitors to Britain. Locally, Lytchett Bay, Holton Pools, Wareham Water Meadow, and the Wytch Causeway are the most reliable sites during the winter. However, it is always worth checking any suitably wet marshy fields over the coming months. An incredible historic record logs a max count of 50 birds at Wareham Water Meadow on December 9, 1984.

The fact that Water Pipits winter in Britain is a curiosity. Water Pipits are an altitudinal migrant, breeding in the alpine meadows of the Alps and the Pyrenees, moving down to lowland freshwater habitats, mainly the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts of southern Europe to overwinter. The 200 or so individuals estimated to winter in Britain embark on a north-west migration in the autumn, highly unusual for a wintering passerine in Europe! Freshwater wetlands including cress beds and sewage works, as well as wet coastal pastures and marshes are favoured winter habitat in the UK.

Water Pipit winter plumage. Photo © Shaun Robson (left) & Ian Ballam (right)

Water Pipit. Photo © Shaun Robson

Late winter and early spring brings about additional challenges as pipits begin to moult their head and breast feathers. The transition sees Water Pipits transform into their gorgeous summer plumage, with bedazzling pink breast and dark ash-grey head. Confusingly, Scandinavian Rock Pipits (unlike our resident breeding population) may also acquire a peachy tint to their breast, although some breast streaking in typically retained, so be sure to scrutinise any moulting birds later in the season.

And of course, please check all Water Pipits for colour-rings! Report any sightings to Birds of Poole Harbour and find out how (and why) to report a ring here ». To date, three birds have been captured and ringed at Lytchett Bay, look out for yellow rings and marked 0K, 1K and 2K…

Water Pipit. Photo © Shaun Robson